When we speak of art in ancient China, we're not just discussing paintings, sculptures, or pottery; we're unraveling a story that stretches across dynasties, philosophies, and the lives of countless individuals from every walk of life. From emperors in their grand palaces to humble farmers in rural villages, and from Buddhist monks in secluded temples to Confucian scholars in study halls, art was not merely decoration—it was a language of spirit, status, and shared identity.

The journey of art in ancient China is rich with complexity, shaped by political shifts, philosophical doctrines, and the personal expressions of countless individuals who contributed to a legacy still admired around the world today.

Imperial Patronage: Power Meets Aesthetics

The emperors of ancient China played a crucial role in the development of art. They were more than rulers—they were tastemakers, cultural curators, and sometimes, artists themselves. The Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), often referred to as the golden age of Chinese culture, saw the imperial court embrace and elevate visual arts like never before. Artists were employed to create murals, court paintings, and religious imagery, often to glorify the reign of the emperor or honor the heavens.

The Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), however, took this to a new level. Emperor Huizong, for instance, wasn’t just a patron of the arts; he was a painter, poet, and calligrapher himself. Under his influence, the Imperial Painting Academy flourished, emphasizing naturalistic details and graceful compositions. The royal court often dictated artistic styles and trends, but the creativity sparked within the court frequently spilled over into the broader cultural landscape.

Spiritual Brushes: The Role of Religion in Artistic Expression

Religion has always been a profound influence on art in ancient China. Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism each played their part in shaping not just what was depicted, but how.

Buddhist art, especially during the Northern Wei and Tang dynasties, introduced grand statues, frescoes, and intricate cave temples. The Mogao Caves near Dunhuang are a vivid example—hundreds of caves filled with painted walls and carved figures, created by generations of monks, artisans, and pilgrims. These were not only spiritual offerings but also masterpieces of collective devotion and artistic prowess.

Daoist art, often more abstract and subtle, focused on harmony with nature, immortality, and cosmic balance. Paintings featuring immortals floating among clouds, celestial landscapes, or philosophical symbols reflected Daoist beliefs and offered artists a rich palette for exploration.

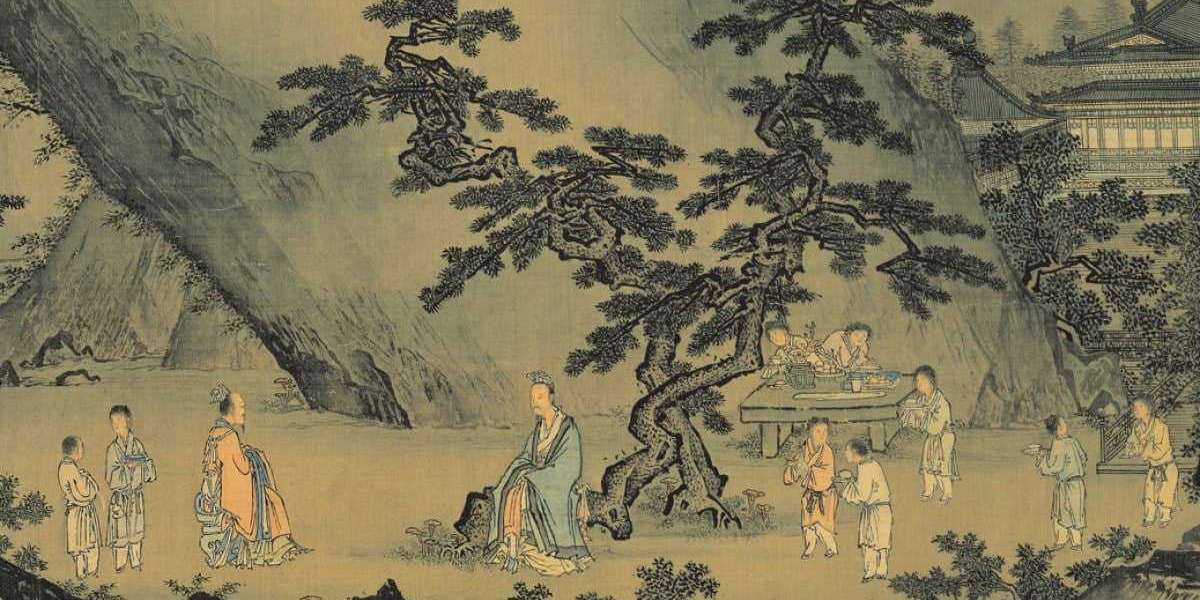

Confucianism, while more scholarly in essence, impacted art through its values. Portraits of sages, ceremonial bronzes, and historical scrolls were created to honor ancestors and uphold social hierarchies. Even the calligraphy, often regarded as the highest form of art, was influenced by Confucian ideals of order, discipline, and moral expression.

Scholars and Literati: Art as Intellectual Dialogue

In contrast to court artists and religious artisans, the scholar-official class—commonly referred to as the literati—developed their own unique approach to art. To them, painting and calligraphy weren’t professions, but philosophical pursuits. During the Song and Yuan dynasties, these scholar-artists produced artworks that reflected personal emotion, poetic thought, and the natural world.

Rather than seeking approval from emperors or religious leaders, the literati used ink, brush, and paper to communicate their worldview. Their art was less about visual perfection and more about inner truth. A single bamboo stalk or a mist-covered mountain in a literati painting wasn’t just a landscape—it was a metaphor, a piece of introspective poetry made visible.

Calligraphy, closely aligned with painting, was revered as a mirror of the soul. The flow of characters, the balance of space, and the rhythm of brushstrokes revealed much about the character and mood of the writer. This emphasis on personal expression made scholar-artists pioneers of a more intimate, reflective form of art in ancient China.

The Artisan and the Everyday: Craftsmanship Among the People

While emperors and scholars left behind scrolls and palaces, the contributions of everyday people to art in ancient China are equally vital. Farmers, village potters, blacksmiths, and weavers all played a part in embedding artistry into daily life.

Ceramics and porcelain, for instance, were not only functional items but also canvases for storytelling and creativity. The famous blue-and-white porcelain of the Ming Dynasty wasn’t just an elite product—it evolved from techniques developed by anonymous artisans in kilns scattered across the country.

Silk production, embroidery, and textile dyeing were also areas where peasant artisans expressed their artistic flair. From intricate dragon robes worn by emperors to embroidered belts and shoes used by villagers, textile art reflected cultural beliefs, regional identities, and seasonal traditions.

Even in architecture, rural artisans crafted timber homes, ancestral halls, and bridges with elegant proportions and symbolic carvings. Every element, from roof tiles to door knockers, had a story to tell.

Nature as a Canvas: Landscape and Symbolism

Nature wasn’t just a backdrop in art in ancient China—it was the subject, the teacher, and the guide. Chinese landscape painting, or "shan shui" (mountain-water), didn’t aim to replicate reality but to interpret its spirit.

Mountains represented strength and permanence, rivers suggested flow and adaptability, and birds or blossoms carried deep symbolic meanings. The plum blossom, for instance, stood for resilience in adversity, while the crane symbolized longevity and peace.

Artists would spend days immersed in natural settings before painting what they had absorbed, not just with their eyes, but with their hearts. These works weren’t just visual escapes but philosophical reflections on life, balance, and the universe.

Materials and Techniques: Beyond the Brush

The evolution of art in ancient China also lies in its materials and techniques. Artists used ink made from pine soot, brushes crafted from animal hair, and paper perfected during the Han Dynasty. The famed Xuan paper, known for its absorbency and texture, allowed artists to create fluid, expressive works that still endure today.

Bronze casting, jade carving, lacquerware, and cloisonné enameling also played significant roles. Each technique demanded patience, precision, and an understanding of material potential. These weren’t merely crafts—they were rituals of discipline and devotion.

Even stone inscriptions, carved into cliffs and monuments, served both aesthetic and political purposes. They commemorated victories, recorded philosophical texts, and left behind a tangible voice of the ancients for modern eyes to read.

Transmission Across Generations

A major strength of art in ancient China was its ability to transmit knowledge across generations. Art schools, family workshops, and written treatises allowed styles and techniques to be preserved and refined. The "Six Principles of Chinese Painting" by Xie He, a 6th-century art historian, still informs artistic philosophy today.

Lineage wasn’t just biological—it was creative. A student might follow a master's painting style or inherit brush techniques passed down over centuries. In this way, art became a living tradition, not a static museum piece.

Final Thoughts

Art in ancient China is not a single story told in a linear fashion. It’s a rich, overlapping mosaic where emperors set trends, monks sought spiritual transcendence, scholars pursued poetic ideals, and artisans infused beauty into the everyday. Each stroke of ink, each carved jade pendant, each temple wall fresco was part of a larger cultural dialogue that continues to inspire.

This unique blend of intellectualism, craftsmanship, spirituality, and imperial authority created an artistic heritage that transcends time. Whether etched into bronze, brushed onto silk, or painted in a cave, ancient Chinese art speaks to a civilization’s soul—and invites the world to listen, observe, and reflect.

If you're passionate about diving deeper into the philosophies, forms, and timeless techniques of ancient Chinese artistry, now is the time to explore authentic artworks, historical replicas, and curated collections. Step into the world of art in ancient China—where every piece holds a thousand stories waiting to be uncovered.